Review by Debbi Voisey

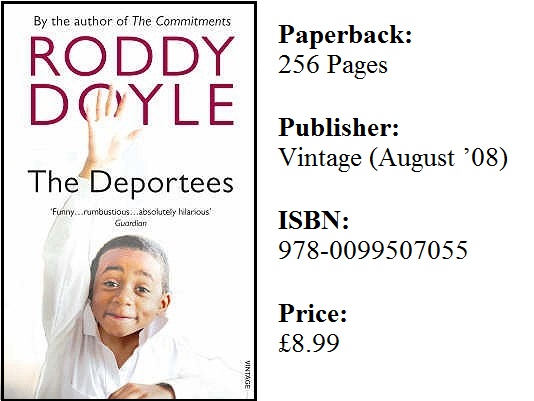

This first collection of short stories by Irish novelist Roddy Doyle is eight years old (the collection, though the stories within it are some years older). That seems ancient in a world that is awash (joyously so) with great emerging storytellers. The reason I chose to re-read it and to review it here is because the subject matter is one which is as relevant today as it was when Doyle wrote it; the immigration (or rather immigrant) experience and the stories that emanate from that.

The Deportees was created from 800-word stories that Doyle wrote each month in the early noughties for Metro Eireann, a then monthly and nowadays weekly Irish Multicultural newspaper that was the first of its kind in Ireland to embrace an ever changing and colourful world. Doyle could see that Ireland was a very different place; black faces were no longer rare, societal issues were no longer simply a case of who was black and who was white. Africans numbered in their thousands. Doyle admired the newspaper and contacted the editor to ask if he could write for it, and the result was a monthly gig that saw him produce his stories through 800 word instalments.

To his own admission, he did not carefully plan the stories. Often when he sent off his current chapter, he would have no plan where to go. Some of the stories have what he calls “tennis racket moments” – referring to the habit of daytime soaps to send their characters “upstairs for a tennis racket” and then never mentioning them again! Some of Doyle’s characters disappeared because he forgot about them.

But when he was focussing and writing, what emerged was solid Roddy Doyle gold. He has an uncanny knack of being able to tap right into barrel of the human condition and to show it with all its flaws, while at the same time injecting the humour that is buried not too deeply within every aspect of life. The stories that resulted from this monthly job number eight in this collection, and they are quite long shorts! They range from 4,800 to 12,000 words. Each of them deals with the same theme; someone born in Ireland meets someone who has moved there. How that is dealt with is different in each case and involve – in Doyle’s own words – love, horror, excitement, exploitation, friendship and misunderstanding.

The first story is titled ‘Guess Who’s Coming for the Dinner?’ Straight away we have the image of the classic movie with Sidney Poitier, so we know what this is about. The subtle re-wording of the title into its Irish translation, however, lets us know that this is a unique slant on the tale, told through the eyes of a very Irish character.

Larry Linnane is a typical dad, of four daughters and one son, living in a noisy, mad, chaotic house. He loves being a father, loves being a provider, and loves especially to be spoilt by his daughters. He was a man who didn’t have to lift a finger:

He knew there was a kettle in the kitchen – he’d bought it himself, in Power City – but, honest to God, he couldn’t have told you exactly where it was.

Roddy Doyle is a master of dialogue, and he uses this in this short story to show us the noise and clamour in the little kitchen where the family congregates. Little snippets of conversation that the girls use to bring “the world home to him.”

Their voices reminded Larry of the Artane roundabout – mad, roaring traffic coming at him from all directions. And he loved it, just like he loved the Artane roundabout. Every time Larry drove onto and off that roundabout he felt modern, successful, Irish.

We are left in no doubt that he loves his family more, and that he is proud of what they have become. Proud that they are beautiful and strong, and confident talking about sex around the table.

And Larry passed the test with flying colours. Nothing his daughters said or did ever, ever shocked him.

Until Stephanie brought home the black fella.

Larry is troubled, confused and surprised at his own reaction to the news that they are to have a dinner guest from Africa. He does not want to be thought of as a racist. He never would have considered himself so, but within him is a fear that even he does not understand. He wants to not be a racist, but his constant thinking of reasons he is not is exposing some prejudice yet to be explored. He is scared of the AIDS thing, scared of someone from a continent rife with civil war. But were they his only objections?

He’d be polite, fair. He’d like the lad – Ben – he’d shake his hand, and hold it long enough to prove that it wasn’t about his skin…

What ensues in an awkward, fiery and soul revealing encounter with a young man who just wants to be accepted and to have money in his pocket.

Doyle cleverly uses the main characters doubts and misgivings to highlight the fears in a lot of us. Larry is not a racist, but Doyle explores the notion that it is normal, in an ever-changing, increasingly culturally diverse world, to have concerns about things we don’t understand – especially when it comes to protecting our loved ones from dangers we cannot see.

Next up, in the story after which the collection was named – ‘The Deportees’ – we get re-acquainted with a character all fans of Roddy Doyle will know and love; Jimmy Rabbitte of The Commitments. It is twenty years on from those heady days of managing Ireland’s most famous soul band, and he hits on the idea of putting together a band formed from all of the nationalities that are on the streets of Dublin. Jimmy is a music expert who was “slagging Moby before most people had started liking him” so nothing could possibly go wrong, right?

First of all he has to convince his wife, and so makes much of looking after the kids and bathing them until they were wrinkly and faint. The wife eventually caves and Jimmy forms his band: “Go ahead,” she tells him, “It’s why I love you.”

This story deals with prejudice at its most basic and ugly. In the midst of his euphoria at bringing all different cultures together and having them embrace the common bond of music which bleaches out all colours, he receives sinister anonymous phone calls from someone intent on criticising and attacking him.

‘New Boy’ deals with a schoolboy newly arrived at a Dublin class. Hints at his past life paint a grim picture of some terrible tragedy in his family – He did not see the men who killed his father – and tells of how he learns quickly the language of his new classmates and how to fit in with this new way of life. He is an outsider but does all he can to fit in. Again, Doyle uses dialogue to show the differences in the two cultures. The boy notices that Miss says “Now” a lot – this is her favourite word – and that Pull up your socks must mean work harder.

The other short stories: ‘57% Irish’ is a darkly comic story exploring how and if Irishness can be measured; ‘Black Hoodie’ shows us how appearances can be deceptive; ‘The Prams’ deals with exploitation; ‘Home to Harlem’ describes a young black Irishman discovering his roots; ‘I Understand’ tells the story of an immigrant starting his new life and getting to grips with his new home.

In all, this collection is a wonderful exploration of the way in which different people cope in different ways with the issue of immigration. Whether they are from the point of view of the immigrant or of the host native taking them into their lives, these stories show without doubt that under the skin we are all the same.

Debbi Voisey was published in The Bath Short Story Award Anthology 2015. In the 90s she edited and wrote articles for a popular U2 fanzine. She enjoyed the journalistic side of the magazine but her heart lies in fiction. She lives in Stoke on Trent with her husband of 26 years, and is currently working hard to get her novel finished while she juggles a job with DHL in Communications. She can be found twittering @DublinWriter and on Facebook at ‘My Way by Moonlight’