Interview by Samantha James

You have had an impressive career as a successful short fiction author, editor, teacher and genre expert, yet your biography simply begins by saying you are a “fiction writer and critic, with a ‘special interest’ in the short story genre”. Where does this interest come from and what makes the form so intriguing for you as a writer and critic?

Like so many others before me, I began writing with the assumption that I was going to be a novelist. Somewhere there is a big metal filing cabinet that I used to get some one big and strong to help with me when I moved house. The top drawer is jammed shut; inside there are notes and drafts towards a novel. Eventually I decided it wasn’t worth some one getting crushed trying to heave this thing downstairs, so I just left it. Who needs a filing cabinet these days? I haven’t completely given up on the novel, but I realised that I’m temperamentally drawn towards the short story because it contains such a concentration and intensity of language, and because you can immerse yourself in the words themselves to a much greater degree than in the longer form. I tend to follow the words when I’m writing, like a dog sniffing a trail. As a critic, looking at writers such as Alice Munro and Katherine Mansfield I find so much to say about a single short story, or even a single word or phrase, because of this richness of language, along with the ambiguities and silences, the ‘before’ and ‘after’ that are unexplained.

Your MA in Creative Writing was completed with a thesis on time and subjectivity in contemporary short fiction – what conclusions did you draw, if any, about how these concepts apply to modern short stories, and how do you apply them to your own work?

Your MA in Creative Writing was completed with a thesis on time and subjectivity in contemporary short fiction – what conclusions did you draw, if any, about how these concepts apply to modern short stories, and how do you apply them to your own work?

This was actually my PhD; before that I completed an MA at Lancaster, which consisted mostly of yet another novel….In the PhD I analysed stories by Munro and Mansfield and Grace Paley, and said a little bit about my own practice. What I concluded was that the short story genre has a special affinity with the passing moment. I’m wary of making grand statements about ‘the’ short story. Short stories can be all kinds of different things. But the form allows me to zip back and forth between past and present, and to merge immediate impressions with memories and digressions. These were things I was doing instinctively; I was also very much influenced by film, especially Nicholas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now. It isn’t so much that I apply the concepts, more that the theoretical concepts resonate with my own practice.

You have stated that your theoretical research has “continued to explore the relationship between the short story and temporality” since you finished your MA. How so?

In addition to my work on Alice Munro, I’ve published journal articles and book chapters on writers including Helen Simpson, Elizabeth Bowen, Malcolm Lowry, Tessa Hadley, A. L. Kennedy, Janice Galloway, Toby Litt and Ali Smith. All of them ultimately focus on how so many meanings, ideas and images can be so tightly packaged in one space. To do that you have to think about how the writer plays with time. So for instance, Helen Simpson’s story ‘Constitutional’ is structured as a circular walk, during which the protagonist reflects on what she sees and what she remembers and speculates about, one train of thought spliced with another.

You have a keen interest in Alice Munro and are known internationally as an expert on her work. What drew you to her? (Besides her tendency to play with temporality which seems like an obvious draw card, was there something else about her writing that spoke to you as an author?)

The beautiful, understated language. When I quote Munro I have to check and proof read very carefully, because her style is so precise and subtle, it can turn on a comma. My first Munro collection was The Beggar Maid. Although Munro belongs to my mother’s generation rather than my own, I still identified with Rose in that collection, and with other Munro protagonists who are educated women from working or lower middle class backgrounds, where practical skills are valued more than reading. I was so hopeless at sewing, I used to hide at the back of the class, pretending. I still can’t tie a shoelace properly.

“Ailsa Cox’s stories play upon the way that the sinister lies just hidden from view… Borges-like, these are stories within stories, where the smallest anecdote gives way to another tale behind it – Cox mesmerises you with her deceptively amiable style – and then bites. The miniature made big, frighteningly big: this is what short stories should be.”

(Robert Shearman)

Is it your intention, when you begin a story, to portray a ‘story within a story’? Is it a conscious decision to make the ‘miniature big’? How do you achieve this, technically?

That’s such a lovely comment, and it shows how other writers can spot a characteristic in your own work that you’re unaware of. Sometimes I do give myself a structure where there are parallel voices or stories within stories – like ‘November’, a story that was written when I first moved to Liverpool in 2004, and is a kind of collage based on my morning walk round Sefton Park with my dog. Bunches of flowers had been left round a tree where a joyrider had been killed. And then some one told me about another death in the park a few years back when a jogger had been hit by a car. Mixed in with this was imagery based around the specific time and place of writing, including snatches from Handel’s Messiah, which I heard in St George’s Hall.

You are the editor of the peer-reviewed journal, Short Fiction in Theory and Practice, and a member of the editorial board of the Journal of the Short Story in English. In addition, you founded the Edge Hill Prize for the Short Story and the European Network for Short Fiction Research. With all this, do you believe the modern short story has enough of a spotlight on it as a genre in modern literary circles?

We can stop moaning about the short story being a poor relation! Short story writers have much more confidence than they used to have, and collections are being reviewed more, and short story criticism is really flowering; see for instance the new Cambridge History of the Short Story in English edited by Dominic Head (yes, it’s a plug, but get your library to order; it’s expensive). We’re just getting to the stage where you don’t have to keep constantly defining ‘the’ short story or talking it up, but can concentrate on fiction in a broader sense. Boundaries are dissolving not just between the novel and short story but between poetry and prose, and between the world of the critic and the world of the short story writer.

Do you have a specific writing process?

I’m a chiseller, which is probably why I’m a short story writer. I sit down and write, straight onto the laptop every morning, and edit as I go along. The first lines are usually pretty clear in my head, but I just blunder onwards from that point. I draft and redraft, and if I make a major change, such as a tense change or a point of view, I have to start at the beginning again. I say I blunder on, but I do have a sense of the architecture of the story, the faint outlines of the story’s final shape. In the later stages, I print off and read aloud. It gives you the right amount of distance to edit the story, but more importantly you can hear rhythm and pace. It takes me ages to get a story right; I’ve just been working on a story that I ‘finished’ a couple of years ago, changing it back from first person to third, and I just hope I won’t change my mind again…

You are a Professor of Short Fiction at Edge Hill University in Ormskirk. What is the best piece of advice you have given a student and why?

You are a Professor of Short Fiction at Edge Hill University in Ormskirk. What is the best piece of advice you have given a student and why?

There are no rules. My writing process completely goes against the advice that’s given to many new writers but it works for me. We’re often told a short story can only deal with one or two characters and a single incident; that’s a handy guideline when you’re talking to a student who’s trying to fit a three volume fantasy epic into a 2000 word story. But it’s not an absolute truth; look at Tessa Hadley’s ‘Married Love’ or ‘The Decline of the Great Auk, According to One Who Saw It’ by Jessie Greengrass (which also breaks the ‘show not tell’ rule).

The Roman philosopher Seneca said: “While we teach, we learn”. Do you believe this is true in the case of teaching short fiction and why?

For me, writing begins with speaking. All of us are natural storytellers, but some find it difficult to preserve the vitality of spoken language on the page. When I teach short fiction, I’m learning about the form itself, but I’m also learning about people. I’m hearing the students’ own personal stories and I’m learning about the surprises life has to bring.

***

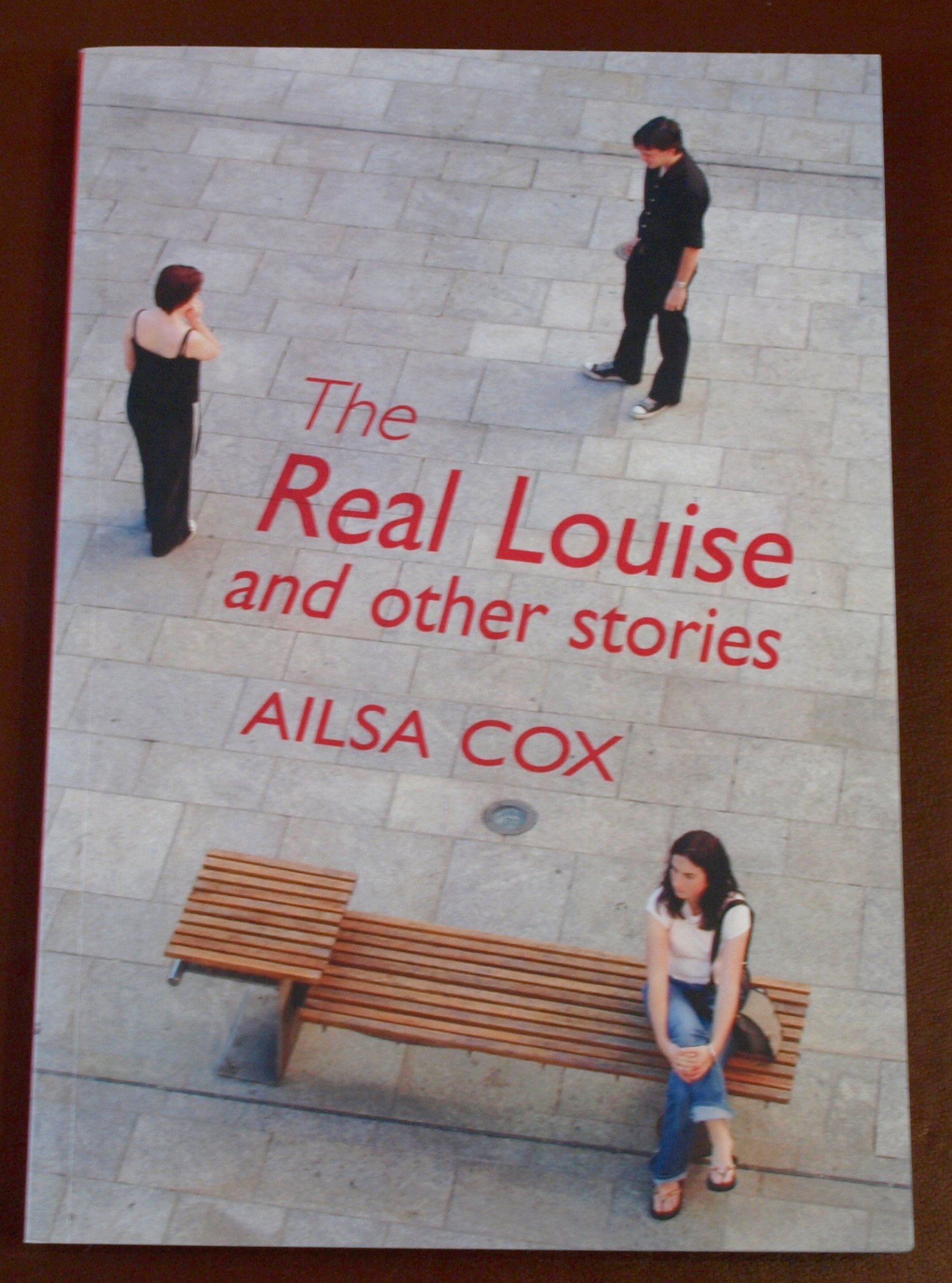

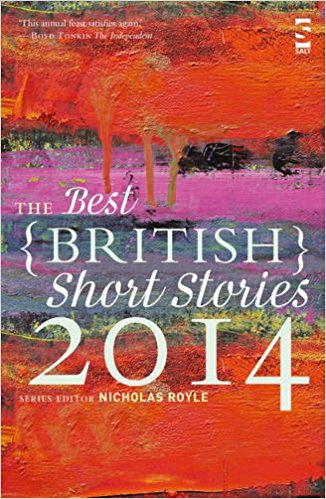

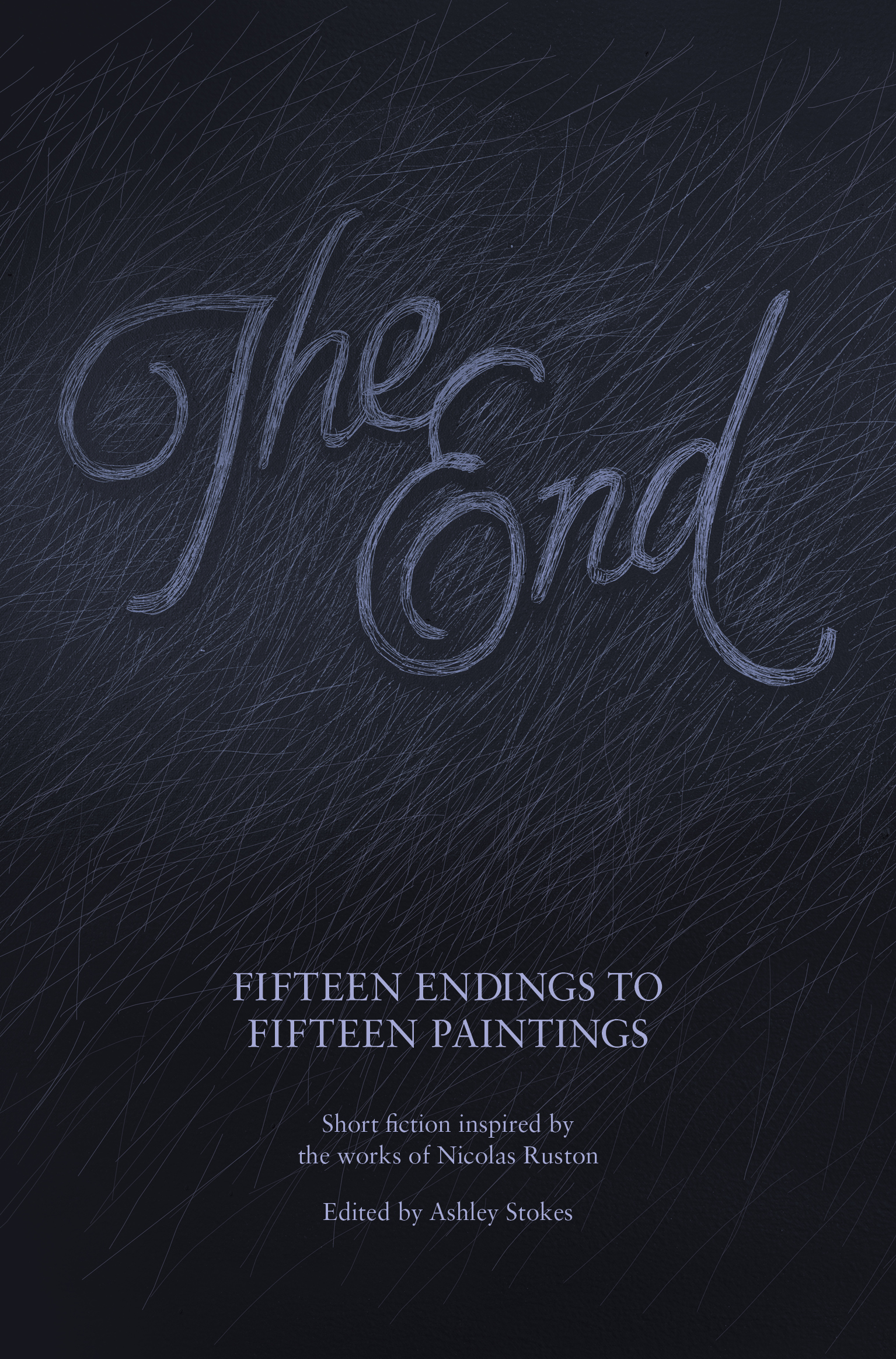

Ailsa Cox’s stories are widely publishing in magazines and anthologies including The Warwick Review, Best British Short Stories 2014 and The End (Unthank Books). Her collection, The Real Louise, is published by Headland Press. Other books include Writing Short Stories (Routledge) and Alice Munro (Northcote House). She is Professor of Short Fiction at Edge Hill University, and the founder of the Edge Hill Prize for a published short story collection. She’s also the editor of the peer-reviewed journal Short Fiction in Theory and Practice and the deputy chair of the European Network for Short Fiction Research. Born in the West Midlands, she lives in Liverpool with her husband Tim Power and her dog Mister B. Ailsa can be found on Facebook and Twitter @ailsacox. Her inaugral lecture on ‘Professor Cox and Mrs Power’ can be found on the Word Factory website.

Samantha James is an Australian journalist, creative writer, avid reader and sometimes-artist. She graduated from Curtin University with Honours in Media, Culture and Creative Writing. As a student she volunteered at creative literary journal dotdotdash. After working as a journalist for a few years, she moved to South Korea to teach English, opening up whole worlds of possibilities. In 2016 she is planning to leave behind her life of structure to focus on creative writing, hoping new travel experiences, impulses and cultures will inspire her words on the page.

Submit an interview to TSS.

Support TSS Publishing by subscribing to our limited edition chapbooks.